There was nothing so unusual about Albert Hermiston.

He was a first-generation American, born in 1920 while his father James – a native Scotsman – worked as a laborer at Camp Kearney in San Diego. His mother died while he was young, and James (who was rapidly approaching sixty years of age) moved young Albert from sunny California to frigid Minnesota. Albert grew up on a farm near Coleraine; unlike many working-class boys of his generation, he completed all four years of high school.

Albert joined the Marine Corps on October 26, 1939, at the age of nineteen. He returned to the city of his birth for boot camp, at which he did well, qualifying as a rifle marksman before graduation that December. Then, as a fully fledged Marine Corps private, he was sent to a dream duty station – the barracks guard at Pearl Harbor, in the territory of Hawaii.

Pearl Harbor in 1940 was the best place for a Marine in his late teens to be. The rumblings of war were present, but most expected that the fighting, if any, would be against Nazi Germany, half a world away. The comings and goings of the fleet, the exotic surroundings, and the promise of a good time on liberty were exciting to say the least – rumors of a threat from the Japanese empire did little more than add to the air of adventure. As a member of Company B (the barracks guard) Hermiston whiled away hours patrolling the naval air station at Ewa Field and waiting for the weekends of liberty at Pearl Harbor. He may have befriended another private in his company, Arthur Ervin.

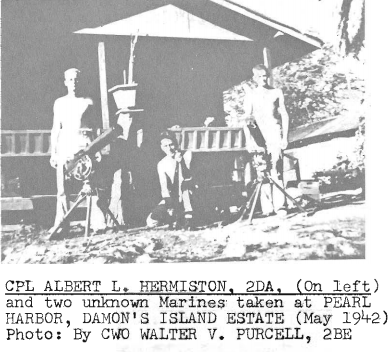

Albert Hermiston was promoted to Private First Class in the spring of 1941. The first stripe brought more pay and prestige; Hermiston may have had visions of glory when summoned to the commanding officer’s quarters and told to take personal charge of a detachment of Marines. His assignment, though, was far from glamorous. “Al was on detached duty on the estate called Damon’s Island, located about halfway between Pearl Harbor and Honolulu, just behind the US Army’s Gen. Trippler Hospital,” recalled Walter Purcell, one of the Marines assigned to Hermiston in October, 1941. “Al would phone the 1st Sergeant [Charles Larsen] on Ford Island each day from his Damon’s Island, where he was guarding 55-gallon drums of aviation gasoline.” (1) The rest of each day was spent trying to stay out of the heat while keeping half an eye on the gasoline. Guard duty, while necessary, was stultifyingly dull.

The attack on Pearl Harbor, just a few miles away, electrified every serviceman in Hawaii. With Ewa and Hickam fields ravaged by Japanese bombers, Hermiston’s supply of gasoline suddenly became much more important – but that wasn’t foremost on his mind. “I was with him during the Jap air raid attacks on 7 December ’41,” said Purcell. “He often said he wanted revenge for the thousands of sailors who really got the worst of it at Pearl Harbor.” (2) Although anxiously awaited, orders for action were not forthcoming to the Damon’s Island detachment, and as the initial fears of Japanese invasion faded, the boredom of guard duty returned.

On July 15, 1942, Albert Hermiston was promoted to corporal. Little else had changed, and some of the garrison were beginning to believe that they were stuck on Hawaii for the duration. The fall of Wake Island and Corregidor had been received, digested, and reluctantly accepted; the more recent news of the successful defense of Midway raised spirits, particularly the stories of Marine fighter and bomber pilots fighting against impossible odds. Another unit, the Marine Raiders, had been present and although they hadn’t seen any fighting carried themselves with the swagger of veterans. The Raiders were based at Camp Catlin on Oahu, but their reputation as swashbuckling hard-chargers spread quickly through the Hawaiian islands and the Corps itself, leaving many a lonely guard or overworked clerk dreaming of acceptance into such an elite unit.

In August, the Marines in Hawaii learned of two operations that piqued their interest. The first was the August 7, 1942 invasion of Guadalcanal by elements of the 1st Marine Division, and the other – much closer to home – was the daring attack on Makin Atoll carried out by the Second Raider Battalion under Lt. Colonel Evans Carlson. The Raiders had landed from submarines, taken a beach under the cover of darkness, and fought a Japanese garrison before withdrawing. Though the raid would later be considered a defeat – the Raiders suffered dozens of casualties without permanently eliminating the enemy garrison – the excitement of the raid spread like wildfire amongst troops starved for good news.

When the Raiders returned to Hawaii, Carlson put out a call for volunteers to fill the gaps in his ranks. Walter Purcell, heartily tired of guard duty, thought he had a chance. “Al, I would like permission to put my name on the Carlson Raider list,” he declared to his corporal. To Purcell’s surprise, Hermiston not only agreed, but followed with a request of his own. “I can’t get away now, but will you put my name on the Raider list too?” he asked. (3)

For some reason, Purcell was hesitant – “At first I wasn’t going to put his name on the list,” he admitted, “but in those days a request from your NCO was like your Commanding Officer’s request… an ORDER not to be questioned.” Purcell, Hermiston, and Ashley W. “Bill” Fisher were interviewed the following day, and were among a handful of hand-picked Marines allowed to join Carlson’s unit. (4)

Raider training, especially in Carlson’s battalion, was far different from that in an ordinary rifle battalion – and Marines who had been kept on garrison duty had to catch up in double time. Raiders were expected to be in peak physical condition, to be self-sufficient, absolutely proficient with dozens of weapons, able to execute intricate maneuvers under the worst conditions, and above all to be totally dedicated to their mission. A frequent question asked during the interviews was “Would you hesitate to kill a man with your bare hands?” Any hesitation or sign of discomfort or surprise was grounds for immediate dismissal. Their watchword was “Gung-Ho” – adopted from the Chinese, it meant to work together for a greater goal, and for the Raiders nearly supplanted their former oath of “Semper Fidelis.”

Corporal Hermiston was placed into Company D of the Second Raider Battalion during training on Espiritu Santo (he also acquired the nickname “Whitey”). (5) The entire unit was anxious to show their prowess in the field; they were perhaps the only men in the world who actively desired a deployment to the stinking jungles of Guadalcanal, especially as their comrades in the First Raider Battalion earned fame from their defense of Bloody Ridge. Their leader, Carlson, was no less impatient and finally secured an assignment – a long-range patrol, lasting thirty days, to collect information at harass the Japanese army far behind the main lines.

The first elements of Carlson’s battalion landed on November 4, and the rest – including Hermiston, who had transferred to Company B – arrived at Tasimboko on November 10. The battalion, reunited at the tiny village of Binu, celebrated the 167th birthday of their Marine Corps with a meager meal of bacon and rice. Hermiston would miss the battalion’s first major fight on Guadalcanal, pulling guard duty with his company while the rest of the unit destroyed a Japanese force near Asamana (ironically, the fighting took place on Armistice Day), but when the battalion began what would become known as the Long Patrol in earnest, it was his Company B that was in the lead.

As a corporal, Hermiston was in command of a fire team of two other men – Privates Richard C. Farrar and Stuyvesant Van Buren, both 20-year-old natives of Chicago. All three answered to their squad leader, Corporal Orin Croft. For the next three weeks, the Raiders made life difficult for the Japanese 230th Regiment, accounting for nearly five hundred enemy killed and many badly needed Imperial weapons and supplies destroyed. As December began the Raiders – short on food and ammunition, and physically exhausted from their campaign – began to work their way back towards friendly lines. Their final objective was the summit of Mount Austen (or Mount Mombula), Guadalcanal’s highest peak and an excellent vantage point, and only two miles from the relative safety of Henderson Field.

The Raiders reached the summit on December 3, but ran into a strong enemy patrol. In the ensuing fight a young platoon leader from Company A, Lieutenant Jack Miller, was shot by a Japanese soldier carrying a captured Thompson submachine gun. “I was about a step behind him,” recalled Raider Ray Bauml. “We took two steps and a machine gun went off and almost blew his entire head off. All his teeth were knocked out, and his tongue was like strips of liver; his whole lower jaw was almost missing.”

Miller was a popular officer, and a particular favorite of Carlson’s. The colonel arranged his men in a defensive perimeter around the summit of Mount Austen, intending to make a break for friendly lines at first light. While the battalion surgeons worked to keep Miller alive and as comfortable as possible, Corporal Croft of Company B was informed that his squad would be leading the descent in the morning of December 4. Croft, in turn, informed Whitey Hermiston that his team would take the first shift on the point of the column. They would be moving fast to get the wounded back to medical care.

Al Hermiston, age twenty-two, stepped off at the head of the battalion not long after daybreak. Slightly behind and to each side walked Farrar and Van Buren. They were so close to home that they could almost see the famous Henderson Field; could almost feel the cool water of a bath and taste a hot meal of something other than captured Japanese rice. The winding path straightened out before them after they’d gone 500 yards, as if welcoming them to safety. Hermiston kept a careful watch on every bush and tree; he’d been a Marine for too long to let his guard down, even this close to the end.

Suddenly, Hermiston stopped. He began to raise his hand, signaling those behind him to hit the deck.

A Japanese machine gun, set up in ambush, opened fire. Al Hermiston was dead before he hit the ground. Richard Farrar dropped his BAR and tumbled like a broken toy. Van Buren dove for a ditch and crawled frantically towards the gun before he, too, was shot.

The second fire team, led by twenty-year-old Cyrill Anthony Matelski of Racine, Wisconsin, was hot on the heels of Hermiston’s group. “We were talking while we saddled up and we lined up about five paces apart when all hell broke loose,” recalled Private Benjamin Carson. “I saw Hermiston go down as we dove off the trail to the right. Matelski took us partly down the slope and we began to encircle the Jap position… We moved about 50 yards and came back up the slope and we all three saw someone in a GI Helmet. Matelski hollered, “Ahoy, Raider”…. It was a Jap in the American helmet and that son-of-a-bitch dropped Matelski with a shot right between the eyes.” (6)

The fight that developed lasted a full two hours, and in the end the Japanese were overcome. Company B abandoned their place at the head of the column and went about the sad business of digging graves for their three fallen comrades. Private Van Buren was hauled out of the gully where he had been lying, shot through the stomach. (7) PFC Duane Paulson appeared from the underbrush, carrying the body of Cyrill Matelski, which he laid down beside Farrar and Whitey Hermiston. The three were buried side by side. A few short hours later, Lieutenant Jack Miller succumbed to his wounds, and was buried alone at the side of the trail. The grieving Marines could plainly see Henderson Field from the gravesite – “within sight of the Promised Land,” as one said.

More than a year went by before the Americans returned to the site of the final skirmish of the Long Patrol.

In 1944, a Graves Registration team located three sets of skeletal remains, all buried together on the slopes of Mount Austen. The body on the right was tagged as Farrar, R. C. (336677), the one in the middle as Matelski, C. A. (346458). The left-most body had no identifying marks – all that remained besides bone was a pair of GI shoes, size 9 1/2. Medical examiners noted a fractured skull – a large hole in the right temporal was consistent with a gunshot wound – and determined that the man had been between 22 and 24 years of age, stood 5’10”, and weighed 155 pounds.

Then then the investigation stopped.

The remains were renamed. Unknown X-94 was buried in Plot C, Row 90, Grave 6 of the Guadalcanal Cemetery.

In 1948, when the cemetery was excavated to repatriate remains, it was decided that X-94 was unidentifiable. He was buried under a stone marked Unknown in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. And just like that, Whitey Hermiston disappeared.

His family and comrades tried to locate him. Walter Purcell, the former private who hadn’t wanted to sign Whitey up for the Raiders, began looking for Hermiston’s grave forty years after the battle, with no luck. Today, Al Hermiston is one of more than 3,000 Marines still officially listed as Missing In Action from the Second World War.

However, with the help of the disinterment directive of Unknown X-94, Hermiston’s service record, and the eyewitness reports of the Raiders themselves, he may be coming home.

This year, Missing Marines will be submitting a case to JPAC, arguing for the identification of Albert Hermiston and the placing of a named headstone on his grave. It is a small step, but one that will hopefully end in bringing a Marine home to his family – which is the very least that he deserves.

And someday, hopefully, the remains of Lt. Jack Miller – whom Hermiston and the others died to get to a hospital – will be recovered from the island, and likewise returned. His grave has never been found.

_____

NOTES:

(1) CWO Walter Purcell, letter to the editor, Raider Patch, January 1982. Page 11.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Ibid.

(5) Croft, Orin. Letter to the editor, Raider Patch, November 1981. Page 14

(6) Carson, Benjamin. Letter to the editor, Raider Patch, November 1981. Page 14

(7) Stuyvesant Van Buren died of his wounds the following day, December 5, 1942.

Contact Historain JOHN Wukovits author of 2009 book “American Commando” on Carlson’s raiders-has an account of ambush in Herimston was killed…

Stuyvesant Van Buren was our mother’s only brother and much missed after his sacrifice. He is buried at

Rose Hill Cemetery in Chicago. He would have had 3 nephews and a niece by his sister Joan Van Buren Keller.

After which there are now 2 boys and a girl to whom he would have been a great Uncle.

The story of Carlson’s Raiders and the sacrifices made by those who fought in World War II ought never be forgotten. It was the job of a generation to assert American might over the farthest places on the globe. The loss of American lives which was necessary for victory is no less tragic for its having become distanced by time. This forum and other means of commemoration are a service to them and to their families. For this, I thank you sincerely.

George M. Keller III , San Diego.

( Never met his Uncle Stuyvesant Van Buren )