Clarence Ell Drumheiser

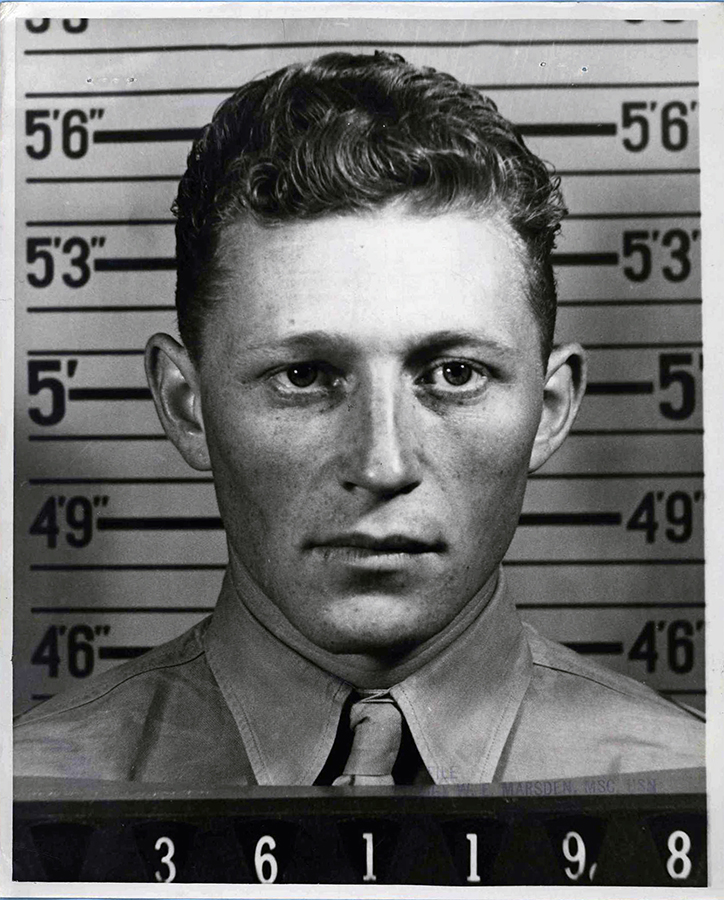

PFC Clarence E. Drumheiser served with Dog Company, First Battalion, 6th Marines.

He was killed in action at the battle of Tarawa on 22 November 1943.

Branch

Marine Corps Regular

Service Number 293127

Current Status

Accounted For

as of 6 April 2018

Recovery Organization

Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency

Read DPAA Press Release

History

Clarence Drumheiser was born in Coalinga, California on 27 February 1922. He grew up in Fresno with his three siblings and two older half-sisters, and attended Fresno Technical High School. Little is known about life in the Drumheiser household. His parents, Malcolm and Delciea “Ella” Drumheiser, were somewhat musically inclined – they co-wrote a ditty entitled It Was Our One Happy Hour Of Memory in 1920, shortly after their marriage – but unfortunately, their union did not last out the decade.[1] Although separated, Malcolm and Ella kept households only three miles apart, and the children may have grown up seeing both parents. Clarence might well have asked his father about military life, for Malcolm had been an Army bugler during the Great War.[2]

When Pearl Harbor was attacked, Clarence decided to do his bit, and joined the Marine Corps from Los Angeles on 10 February 1942. He spent his twentieth birthday in boot camp at MCRD San Diego, and upon completion of training was assigned to Company D, First Battalion, 6th Marines – a venerable unit that had recently returned from garrison duty in Iceland. For more than six months, Drumheiser trained in the boondocks surrounding Camp Elliott, California. He learned the job of every man on his machine gun crew, and the role of his NCOs, too. The First Battalion received extra training in the use of rubber boats, and Drumheiser spent many exhausting days padding a bulky craft through the California surf. He did well, and quickly earned a promotion to Private First Class. There was even some time to relax. “Despite the strenuous training and the rapt following of the war news… the Marines’ mood was ebullient and contagious,” notes a regimental history. “Liberty was granted freely…. Combat was a tomorrow somewhere in the hazy future.”[3]

In mid-October 1942, Drumheiser’s battalion boarded the SS Matsonia, and set sail for New Zealand. The converted luxury liner fairly sped across the Pacific at a speed of twenty knots. Aside from an abbreviated “Shellback” cemetery upon crossing the equator – at which Drumheiser was initiated into the Ancient Order of the Deep – the twelve day voyage passed without incident. Their arrival in Auckland was heralded by the division band, a host of ferries and tugs, and the embarrassing realization that they were supposed to be in Wellington.[4] The pattern of training and liberty began again. A notable addition to the regimen was a series of lectures from veterans of Guadalcanal, scarecrow-thin and Atabrine yellow. The 6th Marines hung on their every word, knowing their turn would come soon.

PFC Drumheiser landed on Guadalcanal on 4 January 1943. Within a week, his regiment was heading for the front lines to relieve the battle-weary 2nd Marines, who hurled friendly jibes: “Well, if it ain’t the Pogey Bait Sixth! How did they get you darlings out of Hollywood?”[5] The final offensive began on 13 January, and within a month the island was finally declared secure. Although they experienced only the tail end of the torturous campaign, the 6th Marines still suffered casualties. D Company alone lost five men killed in action, and one man who simply disappeared while on patrol. Clarence Drumheiser himself escaped wounds or injury, but might have been among those who suffered from malaria, dengue, or the “jungle crud” before departing Guadalcanal on 19 February.[6]

First Battalion, 6th Marines returned to New Zealand and settled into Camp Russell, their home for the next eight months. The first few weeks of “maximum liberty” – the Marines were too depleted for aggressive training – were welcomed by all hands, who quickly fanned out to explore Paekakariki and Wellington. Eventually, a stricter schedule prevailed as replacements arrived for training and recently promoted officers and NCOs learned their new roles. By early summer, the battalion was fully recovered from the strains of Guadalcanal. Unit muster rolls do not record many events of military significance in PFC Drumheiser’s life during this time, aside from a few spells in the sick bay. He would have participated in all the routine training with his machine gun team, and partaken of every liberty he had available. There were dances at the Hotel Cecil, dates to the movies, snacks at the milk bars and drinks at the regular bars, which occasionally ended in brawls. Drumheiser might have had a steady girlfriend in New Zealand; at the very least, he probably had friends who got hitched in these happy months of 1943. “Memories of Guadalcanal faded into the distance,” notes a regimental history. “Yet always lurking in the backs of their minds was the thought that this couldn’t go on much longer. There was a war out there, a big one, and they had a part to play.”[7]

On 20 November 1943, PFC Drumheiser paced the deck of the USS Feland. He had been aboard the transport for nearly three weeks, and every man in his battalion was getting antsy. A big battle was brewing over the horizon; they could hear the booming of naval guns and see smoke rising from an island in the distance, but hard information about the progress of the fighting was frustratingly hard to come by. Many of the men were openly disgruntled at being kept in corps reserve aboard ship. When would be their turn to land on Betio?

The decision to commit the 6th Marines was made on D+1, 21 November. First Battalion had trained with rubber boats back in California, and so they were selected to paddle ashore in the little craft and land on Green Beach, Betio’s western coast. The beach was secured, but Japanese barbed wire snarled some of the rubber boats, and they had to navigate carefully through a mine field. Two LVTs accompanied the boats ashore, but one hit a mine, and 1/6 spent their first moments ashore searching for survivors and offload badly needed supplies from the surviving vehicle. Later that night, they were bombed, and PFC Drumhiser probably sheltered gratefully in a shallow foxhole while listening to the missiles swish down. Fortunately, no damage was done.

In the morning of 22 November – D+2 – the First Battalion attacked eastward along the Black Beaches and the main runway of Betio’s vital airfield. They were fresh and eager for a scrap; the advance was vicious and casualties one-sided in the Americans’ favor until early afternoon. Japanese resistance increased as they were backed into a corner, and a few men who escaped being hit were felled by heat prostration; Betio’s sands were “white as snow and hot as red-white ashes from a heated furnace,” in the words of D Company’s First Sergeant.[8] B Company, to which PFC Drumheiser’s 2nd Platoon was attached, held the right flank up against the sea and suffered heavy casualties in the afternoon. As evening approached, the advance was called off and the battalion set up defensive positions in case the Japanese tried to attack under cover of darkness. A heavy machine gun, like the one Drumheiser’s squad carried, was a vital part of this defensive arrangement, and would have been sited to maximize its field of fire. Its crew also knew that once they opened fire, they would be the first target of a charge.

About sundown, we were getting ready to dig in for the night and we were waiting for orders to get to our positions when the counterattack began. We all hit the ground and started for cover. At this time Baumbach was killed and at the same time Drumheiser was killed. John Gillen set up his gun and after firing a few bursts, he was also killed and one of the other fellows took over, and he was wounded and had to leave and then I moved over and took over. At that time I saw on the side of the bunker [to his left] one of the squads trying to set up their gun and after a few seconds, I saw one of the boys go down by machine gun fire, and later learned that it was the boy Hatch. At this time I was relieved of the gun and sent to help another squad.[9]

Private Wayland Stevens, D/1/6th Marines

The Japanese made two light pushes against 1/6’s line, sacrificing about fifty lives to search out Marine machine gun positions. It was a nervous, noisy night, culminating in an all-out banzai charge at 0400 hours. B Company, with the survivors of 2nd Platoon attached, fought back savagely. With the help of some close artillery support, the line was held, and in the morning some 325 Japanese lay dead in the blasted No Man’s Land.[10] The tired defenders were relieved by fresh troops around daybreak. After a brief respite, during which time the reserves took care of any surviving Japanese in the immediate area, small groups from 1/6 went out in search of their dead and wounded. Private Stevens volunteered; he knew where to find several of the bodies.

After the area where [the] counterattack occurred was cleared, several of the boys in the platoon went up and picked up the boys that were killed and buried them in the same location, leaving one dog tag on the body and the other on the marker that we placed on the grave.

I was a member of the burial party and assisted in the digging of the graves in order to bury the remains of the Marines who were killed in the counterattack. We dug the graves just about four feet deep and before burying any of the boys, we searched them for their personal effects and also to make sure they had identification tags.

At the time we buried them, we found ourselves some trash wood that we inserted into the ground and then finding some old mess gear, we scratched in the names of the dead boys on the mess gear and hung this equipment over the board that signified the grave of the Marine dead. One of the identification tags we left on the body and the other tag, we just loosely hung the chain over the top of the board and just placed the mess gear bearing the scratched identity of the deceased on that.[11]

Sergeant Percy O. Robbins led the group that found and buried the remains of Drumheiser, Baumbach, Gillen, Hatch, PFC Jack E. Hill and Private Jacob Cruz in a miniature cemetery near their fighting position.[12] A few days later, the survivors gratefully left the smoky, reeking island behind, never to return.

Officially, Clarence Drumheiser was reported as killed in action by “shrapnel and gunshot wounds, head.” On 23 November 1943, he was buried in “Gilbert Islands Cemetery” – Marine Graves Registration records noted his body lay in “#18, Grave B, East Division Cemetery.” Interestingly, this information differs from the details provided for his friends Baumbach, Gillen, Hatch, Hill, and Cruz: they were buried in “Grave D.”

The Navy eventually established a memorial cemetery over the top of the original East Division Cemetery, designated Cemetery 33. They took down the original markers and laid out regulation plots, which looked much more military but had no correlation to the men buried on the site. When the 604th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company arrived in 1946, they decided to start their exhumations at Cemetery 33 – the largest one on the island. “From a rough count, there should have been approximately 400 bodies buried here,” read their report, “but at this point our difficulties began. After two days of excavating no bodies had been recovered. This created much concern.” Father William O’Neill, the chaplain who oversaw the creation of the East Division Cemetery in 1943, suggested digging diagonally across the site, and “by a series of prospect excavations and narrow trenches, the middle [longest] row was found first.”[13] This was “Grave B” – supposedly the spot where Clarence Drumheiser was buried.

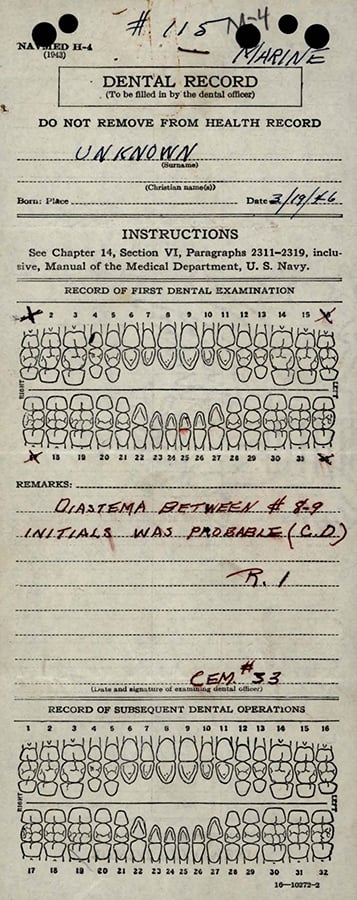

The 604th found 129 bodies in Cemetery 33; due to the lack of identification tags and poor preservation of the remains, fewer than 25 of these could be identified prior to reburial in the Lone Palm Cemetery. One of these was a young man, eighteenth of 44 in Row B, who was exhumed on 19 March 1946. No identification tags were found with his remains; his clothing, if any could be found, bore no recognizable marks. He had been buried with a few meager possessions: a hunting knife on a belt, a pair of pliers, a compass, a bottle, a spoon, and a paintbrush.[14] A dental technician drew up a tooth chart for “Marine #115,” noting a distinctive space between the two front teeth, but little else of value was revealed. “Tooth charts were not as much value… as was originally estimated,” noted the GRS report.[15] The remains were designated “X-25” and reburied in yet another cemetery, designated Lone Palm, where the 604th were collecting the dead.

Later that year, Lone Palm was itself exhumed, and the remains were sent to the Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii. There, trained anthropologists and technicians sorted through bones and personal effects, compared skulls against dental charts, and managed to identify several more of the remains, including Corporal Paluch of D/1/6. A distressing number, however, remained unidentifiable – including the young man now known as X-25. He was described as “a fairly tall, rather slender brunette with narrow hips” with “a noticeable gap between the upper front teeth.” By the time he reached Hawaii, his only personal effects were his belt and his knife sheath. A sharp-eyed tech noted a marking on the leather sheath, which appeared to read “C D” but did not investigate farther. On 23 March 1949, X-25 was buried in Plot E, Grave 135 of the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific as an unknown.

Excerpts from the original CILH lab report into Betio X-25.

In October 2016, Unknown X-25 was exhumed for a final time, and returned to the Honolulu laboratory. He was identified as Clarence Ell Drumheiser on 26 March 2018; the official notification was accounted for as of 6 April.

Drumheiser was buried in Dallas-Fort Worth National Cemetery on 7 December 2018.

[1] Library of Congress Copyright Entries, Catalogue of Copyright Entries Pard 3: Musical Compositions vol. 15, no. 8 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1920). This same volume references two other lyrics by Malcolm: “Bluebeard” and “Tell Them At Home I Am Sorry.”

[2] While he never fought overseas, Malcolm Drumheiser left the service with a twenty percent disability His condition evidently worsened as time went on; when he registered for the draft in 1942, he was unemployed and living off his pension for “total permanent disability from last war.”

[3] William K. Jones, A Brief History of the 6th Marines (Washington, DC: Headquarters and Museums Division, Headquarters USMC, 1987), 50.

[4] Ibid., 51.

[5] Ibid., 54.

[6] Muster rolls for 1943 indicate that Drumheiser was confined to sick bay multiple times, although reasons are not given. It was not unusual for men to suffer relapses of tropical diseases during their training in New Zealand.

[7] Jones, A Brief History of the 6th Marines, 63.

[8] Joseph H. Alexander, Across The Reef: The Marine Assault of Tarawa (Washington, DC: Marine Corps Historical Center, 1993), 36.

[9] Wayland Stevens, letter dated 20 April 1948, in Robert J. Hatch Individual Deceased Personnel File.

[10] James R. Stockman, The Battle for Tarawa (Washington, DC: Historical Section, US Marine Corps, 1947) 53-54.

[11] Stevens letter, 20 April 1948.

[12] Wayland Stevens to Mrs. Myrtle Hatch, letter dated 17 April 1947, in Robert J. Hatch Individual Deceased Personnel File. Stevens said that “Jack Hill, Edward Baumback [sic] Jacob Cruz, John E. Gillen, and Edward [sic] Drumheiser” were “all buried at the same place [as Hatch].”

[13] 1Lt. Ira Eisensmith, “Memorandum to Chief, Memorial Branch, Quartermaster Section, Army Forces, Middle Pacific, 3 July 1946.” One man reportedly buried in Row D was found – PFC Manuel Nunes, Jr. (M/3/8th Marines) – but he was in Grave 33, the very end of the row, and the 604th evidently did not search further. Other remains in the middle of the cemetery were overlooked completely and left behind.

[14] Schofield Mausoleum #1, Betio X-25, Individual Deceased Personnel File.

[15] Eisensmith, “Memorandum.”

Decorations

Purple Heart

For wounds resulting in his death, 22 November 1943.

Next Of Kin Address

Address of mother, Mrs. Ella Drumheiser.

Location Of Loss

PFC Drumheiser was killed in action along Betio’s southern shore.