ACCOUNTED FOR

|

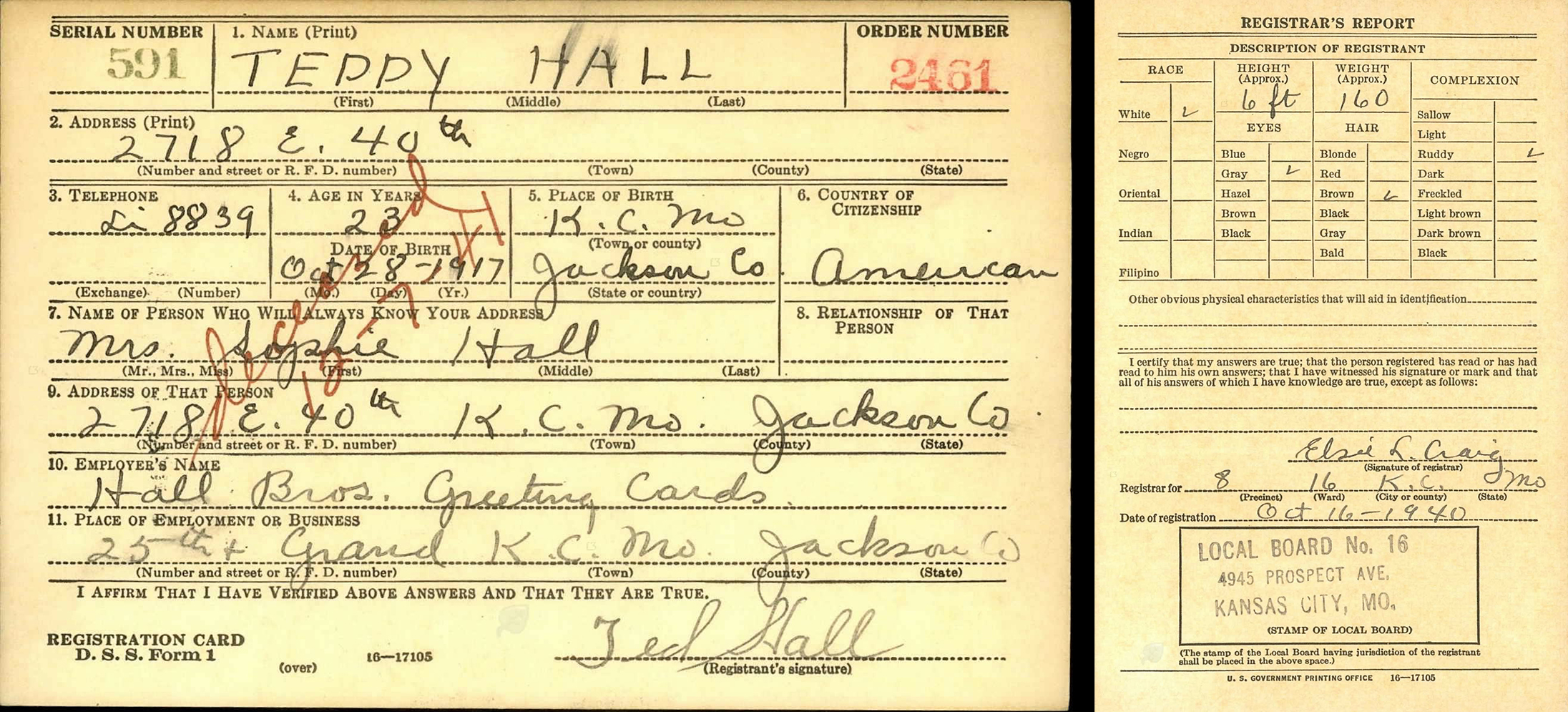

NAME Ted Hall |

NICKNAME Teddy |

SERVICE NUMBER 311258 |

|

| UNIT Marine Detachment, USS Oklahoma |

HOME OF RECORD 2718 East 40th Street Kansas City, MO |

NEXT OF KIN Parents, Walter & Sophia Hall |

||

| DATE OF BIRTH October 28, 1917 at Kansas City, MO |

ENTERED SERVICE June 16, 1941 at Kansas City, MO |

DATE OF LOSS December 7, 1941 |

||

| REGION Hawaiian Islands |

CAMPAIGN / AREA Pearl Harbor |

CASUALTY TYPE Killed In Action |

||

| CIRCUMSTANCES OF LOSS Private Ted Hall was on duty aboard the battleship USS Oklahoma when she was sunk by Japanese aircraft at Pearl Harbor. He was not seen after the attack, and was declared dead as of 7 December 1941. Hall’s remains were recovered from the Oklahoma during salvage operations and buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific as unknown. He was identified and accounted for on 16 January 2019. |

||||

| INDIVIDUAL DECORATIONS Purple Heart |

LAST KNOWN RANK Private |

STATUS OF REMAINS Accounted For DPAA Press Release |

MEMORIALS Arlington National Cemetery USS Oklahoma Memorial Honolulu Memorial |

|

Theodore “Teddy” Dombrowski was born around the year 1918, the third son of Steve and Sophia Dombrowski of Kansas City. His parents divorced not long after the birth of their fifth son, John, in 1926; two years later, Sophia remarried to Walter Hall. Walter officially adopted all five Dombrowski boys, and they in turn adopted his surname. The Hall family – Walter and Sophia, plus Leon, Edward, Teddy, Thomas, and John – settled into a new home on the Missouri side of Kansas City.

Teddy Hall grew into a handsome, good natured young man, attending school during the week, and spending Sunday mornings at Oak Park Christian Church with his close friend, Donald B. Lowery. Evidently tiring of formal education after his freshman year at Central High School, Hall went to work for a familiar Kansas City business – Hallmark Cards – as a service clerk (1). He kept in close touch with Don Lowery while the latter attended Missouri University in Columbia, exchanging local news and musing about the conflict developing overseas.

In June of 1941, Teddy typed up a missive to Don. Both young men were registered with their local draft boards, and they might have had friends who were called to serve. Being drafted meant going to the Army, wrote Teddy, and going to the Army meant an uncomfortable life in barracks. Why not beat the system and volunteer for the Marine Corps? Don was easily persuaded. On 16 June 1941, just a few days after this exchange, Teddy and Don enlisted in the Marine Corps and were packed off to San Diego for several weeks of boot camp.

Privates Hall and Lowery were both chosen for sea duty, and were sent up to the Hunter’s Point Naval Shipyard with orders to report to the USS Oklahoma. Their first sight of the venerable battleship was less than impressive: she was in dry dock awaiting repairs to a broken propeller shaft. It was an excellent opportunity for the classic Navy pastime of chipping paint, and the two junior Marines quickly became acquainted with the tools of this trade. Sailing day on 3 October 1941 brought relief and a growing excitement as the ship drew ever closer to the territory of Hawaii. After passing several tantalizing tropical islands, the Oklahoma put in at Pearl Harbor on 12 October.

As junior privates – and reservists at that – Hall and Lowery were decidedly at the bottom of the Marine detachment’s duty list. They frequently found themselves stuck on mess duty, carting trays of food from galley to mess hall, then hauling the dishes away to the scullery. Being detailed with a buddy made the work go faster, though, and the chowhound Hall – “no matter how bad the food was, he never missed a meal” – was a regular fixture in the Marine galley.(2) He and Lowery worked together, bunked together, and went on liberty together.

It seemed that half of the Oklahoma’s crew was on the liberty list for the first Saturday in December, 1941. The Christmas season was approaching, and Honolulu merchants did a booming trade selling exotic tchotchkes and trinkets to haole servicemen. Privates Hall and Lowery were in the market for presents, and spent their day wandering through the shops and stalls. “We went out Christmas shopping and mailed our Christmas cards,” Lowery recalled. “We came back and sat on the fantail of the ship. We talked about old times and discussed the Japanese negotiations that were going on and made the facetious remark that we hoped if anything happened we’d have a good strong hull beneath us.”(3) Thus comforted, the two friends headed for their bunks.

“That morning [Sunday, 7 December] I guess I was vaguely aware of Ted’s shaking me, asking about breakfast,” recalled Don Lowery in 1973. “I didn’t even open my eyes. I didn’t feel the food was worth it.”

Suddenly it seemed just like everything was going upside down. Everything was shaking. At that point somebody said we were having a practice bombing. The first reactions were some expletives of profanity. Then someone got on the intercom – it was the officer of the day – he said “man the antiaircraft battery.” Then he repeated the command and said “this is a real air raid.” My first reaction was “there’s some drunk sailor or Marine who’s going to get locked up for doing that.”

Lowery ran for his battle station, but found his path blocked. The ship was beginning to list, and soon the Marine was standing in knee-deep water. In the confusion of the moment, he and another friend flipped coins to see if they should “go up and get shot [or] stay and go down with the ship.” They reached the fantail and were climbing down a lifeline when the USS Arizona erupted into a massive fireball. Lowery was flung overboard by the shock wave, but managed to reach safety aboard the USS Maryland, where he stayed for the next several days.

Some time after the attack, Lowery learned what had happened to Teddy Hall.

He went down to breakfast that morning. I was told he was down there [in the galley] when one of the torpedoes hit and one of the gear lockers overturned on him. He was crushed.(4)

Back in Missouri, the Hall family was preparing for what should have been a joyous season – the oldest son, Leon, was getting married just before Christmas. When Walter and Sophia returned from the wedding, they received the telegram reporting that Teddy was missing in action. Within a month, he was officially declared dead. The four surviving brothers all joined the service – two in the Army and two in the Navy – and, fortunately, survived the war. Sophia, however, never fully recovered from Teddy’s loss; her plight was probably magnified by the determination of his remains as non-recoverable.

Following a painstaking engineering operation, the Oklahoma was righted and refloated in early 1944. While salvage crews cleaned and removed anything of possible military value – and Sergeant Don Lowery returned to collect several personal effects from his locker – other teams searched through years of accumulated muck for human remains. Navy diver Edward C. Raymer was tasked with taking a civilian reporter aboard the ship:

We reached the third deck, and Burns asked me about dead bodies: how many had been found, what was done with them, how they could be identified. I explained that the medics sorted through all the sludge and debris for bones. Then they placed approximately two hundred bones in a bag, which represented the number in a human body. The bag was sent to the army hospital, where a chaplain performed services for the remains.

According to the Oklahoma’s muster records, four hundred of the crew perished aboard her. I finished by saying I was glad it wasn’t my job to explain to the sailors’ families why their loved ones remained unidentified. The reasons could seem very offensive to them.

Slithering through the ankle-deep filth, Burns caught himself as his foot struck something on the deck. He cried out in revulsion when he found it was part of a human body. “My God, I’ve stumbled over a leg. It even has a shoe on what’s left of the foot.”

– Edward C. Raymer, Descent Into Darkness: Pearl Harbor, 1941, A Navy Diver’s Memoir

The remains recovered from the Oklahoma were buried in fifty-two mass graves in Halawa and Nuuanu Cemeteries on the island of Oahu. At the end of the war, the graves were exhumed with the intent of identifying as many of the dead as possible before reinterment in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. Dr. Mildred Trotter, one of the anthropologists in charge of the Central Identification Laboratory, was dismayed to note that “common graves consist[ed] of bones of a kind buried together (i.e. one casket was filled with skulls, another with femurs, another with hip bones and so on)” – a strange decision that “added greatly to the difficulty of the undertaking.” Although her technicians made “a very honest effort… to segregate all the remains from the Oklahoma,” Dr. Trotter admitted that it would take “a very long period (years)” and “different circumstances” to fully separate all the remains. Only 49 men could be identified by the end of 1949; the remainder were buried in 46 common graves in Honolulu.

In 2015, an official directive was passed to exhume the graves of the Oklahoma’s final crew. Modern science and DNA analysis provided the “different circumstances” Dr. Trotter’s note required, and more than 100 of the crew have so far been identified. Private Teddy Hall’s remains were among them; he was officially accounted for on 16 January 2019.

_______

NOTES

(1) The 1940 census indicates that Hall had completed one year of high school and had not attended class in the previous calendar year. Despite sharing a surname with the founders of Hallmark, Ted was no relation.

(2) Jean Haley, “Japanese Bombs Exploded Lazy Pearl Harbor Sunday,” The Kansas City Times (7 December, 1973), 6C.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Ibid.

On this 75th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor and loss of our dad’s brother, Ted Hall, we remember the wonderful stories our folks told us about the uncle we never got to meet. He was handsome, smart and a really nice guy. He and Don Lowery went to Oak Park Christian Church together. There’s a typewritten letter from Ted before he came back from MU in Columbia in June, 1941 to Don suggesting they sign up for the Marines instead of being drafted in the Army where they’d have to live in barracks. Within a few days of that letter, they both joined the Marines.

I had a chance to visit with Don before he passed away and record some of his memories about Ted and their experiences together in the Marines and aboard the USS Oklahoma.

Ted was the first employee of Hallmark Cards (then named Hall Brothers–no relation to Ted, my dad and their three brothers) to die in WWII. I have a letter from the Executive Vice President of Hallmark written in 1976 to the family saying he worked with Ted and what a great guy he was.

There’s an article in The Kansas City Star (or Times) about the good and bad day of December 24, 1941 for my grandparents, Walter and Sophia Hall. After returning home from the wedding of their oldest son (our parents, Leon and Martha) that evening, they received notice that Ted was missing in action. I understand my grandmother Sophia Hall was never the same after Ted died. She died ten years later from cancer and a broken heart. She was the proud mother of five boys who all served in WWII: Leon-U.S. Army, Eddie-U.S. Navy, Ted-U.S. Marine Corps, Tom-U.S. Army Air Force, John-U.S. Navy.

We hope someday soon Ted’s remains will be positively identified in the special government program that is attempting to identify the remains of the USS Oklahoma soldiers through DNA.

Rest in peace, Uncle Ted. You are not fogotten.

Trudy Hall and Joanne (Hall) Oberndorfer

I just witnessed your uncle’s return via a Southwest flight into the Baltimore airport. So moving. As a military wife, I am so happy for your remaining family members to finally receive closure. God Bless, Kim Barron

I was also at the airport in Baltimore this afternoon and was honored to witness the arrival of Pvt. Hall. God bless your family and may you all find peace and closure as your loved one is laid to rest at Arlington.

Beth Stolts