Lyle Ellis Charpilloz

PFC Lyle E. Charpilloz served with Fox Company, Second Battalion, 8th Marines.

He was killed in action at the battle of Tarawa on 20 November 1943.

Branch

Marine Corps Regular

Service Number 315407

Current Status

Accounted For

as of 26 September 2017

Recovery Organization

Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency

and

History Flight 2014 Expedition

Read DPAA Press Release

History

Lyle Charpilloz was born in Silverton, Oregon on 3 March 1926 – sixth in a family of eight kids raised by Abel and Alice (Eggleston) Charpilloz. He grew up on a sheep farm in Marion County, and attended a one-room schoolhouse in Silver Cliff.

Young Lyle grew up quickly: “you looked at him as being a lot older than he was,” recalled his sister, Marie Galloway. Farm work was tough – on one occasion, Lyle cut off the tip of a finger while clearing timber for utility poles – and the Charpilloz household was not entirely happy. Abel was often absent; when home, he mistreated Alice to the point where Lyle was forced to protect his mother. (In 1939, Alice divorced Abel and won custody of the children.)

Although not particularly big for his age – he stood 5’8″ tall and weighed 139 pounds – Lyle was able to pass for an older boy. In the summer of 1941, he determined to lie about his age and join the Marine Corps. It was no secret to the family – “everyone knew he was doing it,” commented Marie – and Alice would have given her blessing to the plan. When he enlisted on 29 July 1941, Lyle entered “1924” for his year of birth: claiming seventeen when he was truly just 15 years old.

The deception worked, and Lyle was soon on his way to San Diego for boot camp.

Immediately after completing boot camp in October 1941, Private Charpilloz was assigned to Fox Company, Second Battalion, 8th Marines – the unit that would be his home for the rest of his life.

Charpilloz was on duty in California when he learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Events unfolded rapidly: by 5 January 1942, his regiment was sea and bound for Tutuila, American Samoa. Charpilloz would spend several months on garrison duty, preparing to repel an expected Japanese attack that never came. During this time, he was promoted to Private First Class.

In late October 1942, the 8th Marines sailed for the Solomon Islands and joined the battle for Guadalcanal on 4 November 1942. Unfortunately, any stories of Lyle’s experiences during the campaign have since been lost; he managed to survive nearly three months of combat without serious illness or injury, and in February 1943 sailed for New Zealand,

During the spring and summer of 1943, the 8th Marines rested and re-trained at Camp Paekakariki outside of Wellington. Despite his youth, PFC Charpilloz could command the respect of new Marines joining the company from the States – he was a combat veteran, after all, with a new tattoo on his left arm. When he wasn’t in camp or in training, Charpilloz was likely enjoying the sights and scenes of Wellington on liberty.

That October – almost exactly a year since they departed Samoa for Guadalcanal – the 8th Marines boarded transports at Wellington for a final round of training exercises. When the ships headed out to sea instead of returning to town, the Marines aboard began to realize that the rumors were true: they were bound for combat once again.

The amphibious assault on Betio, Tarawa atoll – Operation GALVANIC – commenced on 20 November 1943. The Second Battalion 8th Marines was given the job of assaulting the easternmost of three landing beaches – “Red 3” – and, once ashore, moving inland to quickly secure the airfield that covered much of the tiny island’s surface. A heavy and morale-boosting naval bombardment convinced many Marines that the task would be a simple one, and spirits were high at 0900 when their amphibious tractors started paddling for the beach.

The Japanese were quick to recover. Shells began bursting over the LVTs. “As the tractors neared the shore the air filled with the smoke and fragments of shells fired from 3-inch guns,” notes A Brief History of the 8th Marines. “Fortunately, casualties had been light on the way to the beach, but once the men dismounted and struggled to get beyond the beach, battle losses increased dramatically.” Most of the beach defenses were still intact, and these were supported by row after row of pillboxes, rifle pits, and machine gun nests.

The Second Battalion, and then the Third Battalion, tried in vain to break through the Japanese defenses, suffering heavy casualties in every attempt. By evening, they were barely clinging to a sliver of beachhead, and the shocked survivors dug in among the bodies of the dead.

Lyle Charpilloz was one of hundreds who fell on the battle’s first day. No eyewitness accounts of his final moments are known to exist; his cause of death was simply noted as “gunshot wounds.”

Nor was there any concrete information regarding the disposition of his remains. Charpilloz was reportedly interred in the “Division Cemetery, Tarawa” – but there were several “Division Cemeteries,” and this information was seemingly applied as a catch-all for any Marine whose body was not identifiable.

In 1944, Seabees from the Tarawa garrison force rebuilt the old Marine cemeteries into beautified memorials. They put a marker for Lyle Charpilloz in Cemetery 33 (Plot 16, Row 1, Grave 15) but this was purely commemorative; his real burial place was entirely unknown.

The 604th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company arrived at Betio in 1946 and set to work exhuming the memorial cemeteries built on top of the original burial grounds. Identification of remains was a serious challenge, and hundreds of men were declared non-recoverable in 1949. Among them was PFC Lyle Charpilloz.

Remains that were recovered but not identified were buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. In March 2017, a DPAA directive ordered renewed efforts to discover their names. “Betio Unknown X-5” was exhumed from Section F, Grave 1227, and sent to a forensic laboratory for analysis. “X-5” was originally recovered from “Cemetery 26“ near Beach Red 2; he was still wearing a pair of Marine boondockers. An identification tag for Oliver Bange was found with the remains – but forensic analysis in 1947 decided that X-5 was somebody else. (Unknown X-10 was subsequently identified as Bange.)

The passage of years actually aided with the identification of X-5. In 2014, non-profit organization History Flight conducted an archaeological dig at the site of Cemetery 26, and retrieved human remains and personal effects which were turned over to the DPAA. Some of these remains were subsequently matched to X-5. A combination of modern forensic efforts – comparison of chest radiographs, dental and anthropological clues, and a DNA sample submitted by Marie Galloway – finally led to the identification of Lyle Ellis Charpilloz on 26 September 2017.

(Since Cemetery 26 was situated some distance from the place where Lyle’s battalion landed and fought, it is not entirely clear how he came to be buried there. One plausible theory holds that Lyle was brought to an aid station or casualty collection point near Red 2, and died of his wounds. He was then buried as an unknown.)

CENOTAPHS

Honolulu Memorial, Tablets of the Missing

FINAL BURIAL

Belcrest Memorial Park, Salem, Oregon

Decorations

Purple Heart

For wounds resulting in his death, 20 November 1943.

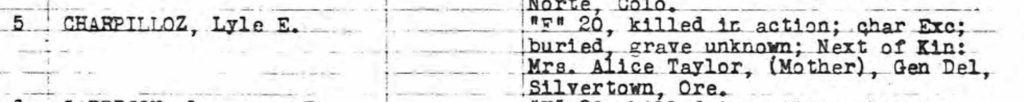

Next Of Kin Address

Address of mother, Mrs. Alice E. Taylor.

Location Of Loss

Charpilloz’s battalion landed on and fought in the vicinity of Beach Red 3.