James Joseph Hubert

Sergeant James J. Hubert served with How Company, Second Battalion, 8th Marines.

He was killed in action at the battle of Tarawa on 21 November 1943.

Branch

Marine Corps Regular

Service Number 280831

Current Status

Accounted For

as of 29 January 2016

Recovery Organization

History Flight 2015 Expedition

Read DPAA Press Release

History

For a complete story of James Hubert’s life, visit Return To Duluth.

James Hubert was born in Duluth, Minnesota, on 12 August 1921. He spent most of his life in the Lincoln Park neighborhood with his parents, Wallace and Mary (Arsenau) Hubert, and younger sister Elizabeth. Family pictures from the 1920s and 1930s show the Huberts as a tight-knit family unit – “a solid home life, but with few luxuries,” in the words of Jay Hagen. “Jimmy” attended school in Duluth, and entered the workforce as a laborer, but as Hagen continues, “employment opportunities were nil and mostly sporadic…. Skilled training programs were nearly non-existent and competition was keen for limited slots in programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps.”

For a time, Jimmy Hubert worked with his father at Northern Cold Storage in Duluth. In 1938, however, he hit upon a new professional trajectory: military service.

Seventeen-year-old James enlisted in the Duluth Naval Reserve in September, 1938. As an apprentice seaman he had the chance to learn new skills while sailing the Great Lakes aboard an antiquated gunboat. Most significantly, it gave him a taste of military life – enough to shape his future career. James spent more than a year in the Reserve, and was honorably discharged on 16 January 1940. He joined the regular Marine Corps the same day, and was soon on his way to San Diego for boot camp. Hubert earned his Eagle, Globe, and Anchor, as well as the silver bar of a rifle marksman, and spent a few months learning the ropes with the 6th Marines

In the summer of 1940, Private Hubert was assigned to duty with How Company, Second Battalion, 8th Marines. For the next eighteen months life revolved around regular duty at Marine Corps Base San Diego; Hubert advanced to private first class, and then to corporal. He evidently never went back to Duluth (not even for the birth of a much younger sister, Mary Katherine), but Jay Hagen notes that “life in sunny southern California wasn’t all work. His extended family included him in many of their gatherings.”

The attack on Pearl Harbor put an end to such peacetime pleasures. By 5 January 1942, his regiment was sea and bound for Tutuila, American Samoa. Corporal Hubert would spend several months on garrison duty, preparing to repel an expected Japanese attack that never came. How Company was a heavy weapons outfit, fielding water-cooled Browning machine guns and 81mm mortars plus a host of supporting jobs – messengers, drivers, ordnance men, and more. Unfortunately, Corporal Hubert’s precise role with the company is not known.

In late October 1942, the 8th Marines sailed for the Solomon Islands and joined the battle for Guadalcanal on 4 November 1942. Unfortunately, any stories of Hubert’s experiences during the campaign have since been lost. He survived three months of combat unscathed; in 1943, his unit was withdrawn from the Solomon Islands and sent to New Zealand.

During the spring and summer of 1943, the 8th Marines rested and re-trained at Camp Paekakariki outside of Wellington. Like many of his fellow combat veterans, Hubert spent several stretches in sick bays and field hospitals – likely the result of a tropical disease contracted on Guadalcanal. He also received a promotion to sergeant, which may have placed him in command of a machine gun or mortar squad.

That October – almost exactly a year since they departed Samoa for Guadalcanal – the 8th Marines boarded transports at Wellington for a final round of training exercises. When the ships headed out to sea instead of returning to town, the Marines aboard began to realize that the rumors were true: they were bound for combat once again.

The amphibious assault on Betio, Tarawa atoll – Operation GALVANIC – commenced on 20 November 1943. The Second Battalion 8th Marines was given the job of assaulting the easternmost of three landing beaches – “Red 3” – and, once ashore, moving inland to quickly secure the airfield that covered much of the tiny island’s surface. A heavy and morale-boosting naval bombardment convinced many Marines that the task would be a simple one, and spirits were high at 0900 when their amphibious tractors started paddling for the beach.

The Japanese were quick to recover. Shells began bursting over the LVTs. “As the tractors neared the shore the air filled with the smoke and fragments of shells fired from 3-inch guns,” notes A Brief History of the 8th Marines. “Fortunately, casualties had been light on the way to the beach, but once the men dismounted and struggled to get beyond the beach, battle losses increased dramatically.” Most of the beach defenses were still intact, and these were supported by row after row of pillboxes, rifle pits, and machine gun nests.

The Second Battalion, and then the Third Battalion, tried in vain to break through the Japanese defenses, suffering heavy casualties in every attempt. By evening, they were barely clinging to a sliver of beachhead, and the shocked survivors dug in among the bodies of the dead.

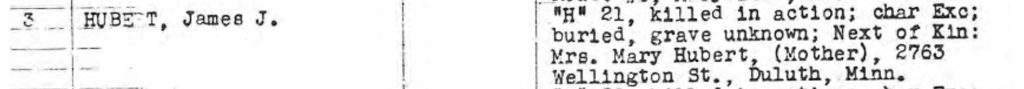

Sergeant James Hubert survived the landing and the first day of the battle, but would not live to see the end. He died of gunshot wounds in the chest on 21 November 1943; unfortunately, the full story of his final moments will probably never be known.

Military records further noted that Hubert was buried in “Division Cemetery, Tarawa.” However, there were three such locations on the tiny island – as well as dozens of other smaller burial grounds. In 1944, a memorial bearing his name was placed in Cemetery 33 (Plot 15, Row 3, Grave 2) by well-meaning Navy Seabees – but his real burial place was a complete mystery.

Jimmy’s youngest sister, Mary, remembered the day his posthumous Purple Heart arrived. “I didn’t understand why [our mother] was crying. I didn’t understand what a Purple Heart was. I just remember when she opened that up. I don’t know if she knew it was coming or whatever, but I just remember her sitting on the floor and crying.”

Post-war searches by the 604th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company also failed to find or identify any remains as Jimmy Hubert. He was declared permanently non-recoverable in 1949 – a decision that devastated his parents.

“No one was able to explain exactly what happened, nor where the remains of their son might be found,” writes Jay Hagen. “The parents of James Joseph Hubert went to their graves with that deep and unresolved sense of loss… Volumes were written following WWII of the impact that the loss of loved one had upon surviving parents. Some never smiled or laughed again, others had hair turn white practically overnight. Still others wept until their own deaths, unable to deal with the trauma of not knowing.”

In 2015, the non-profit group History Flight conducted an archaeological dig at a shipyard on Betio. This expedition, the result of years of research and data supplied by GPR and a cadaver dog, hoped to find one of the missing mass graves near Red 3 – a place called “Cemetery 27” by the Navy; “8th Marines Cemetery #2” or “Division Cemetery 3” by the Marines. Some forty men were reportedly buried in the area – some identified by name, others unknown. Postwar attempts to find the grave had failed; a large marker commemorated the fallen, but no bodies were buried nearby.

The History Flight team started their operations near the spot where PFC Herman Sturmer‘s remains were found in 2011. They soon discovered an original “burial feature” containing the remains of several men wearing Marine Corps boondockers. One of them still wore a legible dog tag with the name “HUBERT, J. J.”

History Flight had not set out specifically to find Jimmy Hubert, but their discovery provided the clues needed to solve the decades-old mystery of his fate. He had indeed been buried in a “Division Cemetery” – in this case, Division Cemetery 3 – in a little trench a few yards inland from the beach. To the north lay a much larger burial feature with the remains of more than forty Marines. The “beautification” process had obliterated any original marker with his name – if one ever existed – effectively erasing all evidence of his burial site until 2015.

On 29 January 2016, James Joseph Hubert was officially accounted for and returned to his family for burial in Minnesota. His personal effects – canteen fragments, a first aid kit, and remnants of boondockers – were donated to the Minnesota Historical Society for preservation.

CENOTAPHS

Honolulu Memorial, Tablets of the Missing

FINAL BURIAL

Calvary Cemetery, Duluth, Minnesota

Decorations

Purple Heart

For wounds resulting in his death, 21 November 1943.

Next Of Kin Address

Address of parents, Wallace & Mary Hubert.

Location Of Loss

Hubert’s battalion landed on and fought in the vicinity of Beach Red 3.

Gallery

For more photographs, visit Return To Duluth.