Above, a member of the 604th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company excavates a suspected burial site. Location unknown, c. 1947-1949. NARA.

Back when I started MissingMarines (ye gods, nearly seven years ago) there was a will and a way to get an unidentified serviceman home. Unfortunately, there was only one will, and only one way, and they belonged to the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command – a now-defunct organization missed by few and mourned by fewer. Many a researcher (and many a good-hearted staffer, too) found themselves professionally stonewalled by a bureaucracy that seemed to care little for its sworn purpose, and viewed the successor agency, the DPAA, with suspicion. It’s no secret I was of this camp, too.

While far from perfect, the DPAA has certainly made good on their promise to increase the rate of recoveries. Their Recently Accounted For list is updated every few days, and they are increasingly willing to work with individuals and non-profits. As an adjunct researcher for History Flight, I’ve gotten to see a bit of how this particular sausage is made; some parts work better than others, of course, but every step (no matter how small) seems to be generally in the right direction.

I’m never so happy to be overwhelmed as when I’m struggling to keep up with recovery news: this never used to be a problem, but it’s the kind of problem one likes to have. There’s a MissingMarines page for keeping track of the most recent recoveries, but until today it has been a little buried in the menu. (We’re doing a lot of content structuring exercises at my day job, and some of that is starting to trickle down.) Fifteen World War II Marines have been accounted for by the DPAA so far this year, out of about 124 total identifications (all branches, all wars). Many of them were exhumed from the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, where they have lain as unknowns since the late 1940s. A few others have been awaiting the right DNA match, or corresponding remains to be returned from the field, or for a family member to accept their identification.

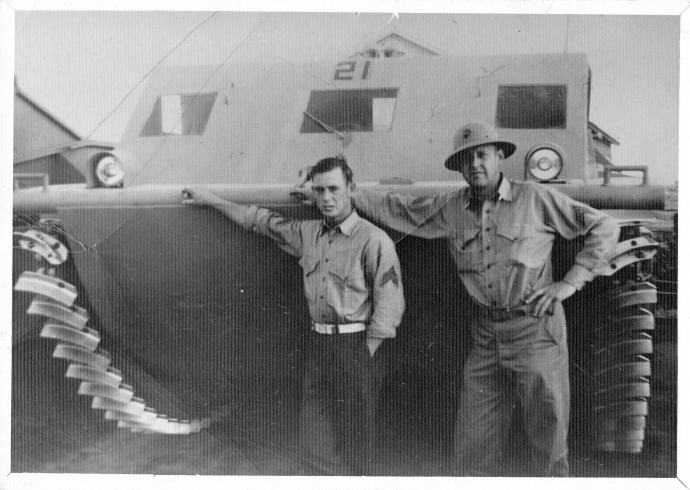

Just yesterday, three Marines were accounted for. Technical Sergeant Harry A. “Bud” Carlsen was a member of Company A, 2nd Amphibian Tractor Battalion. An ace auto mechanic before the war, Carlsen enlisted two weeks after Pearl Harbor and quickly worked his way up to a role as a senior maintenance NCO for the ungainly LVTs of his company. He served as the repair section chief on Guadalcanal, where he saw little action but contracted malaria. Not long after reaching the shores of Betio, the burly 31-year-old Carlsen was shot in the abdomen, then in the head. He died on 20 November 1943.

Just yesterday, three Marines were accounted for. Technical Sergeant Harry A. “Bud” Carlsen was a member of Company A, 2nd Amphibian Tractor Battalion. An ace auto mechanic before the war, Carlsen enlisted two weeks after Pearl Harbor and quickly worked his way up to a role as a senior maintenance NCO for the ungainly LVTs of his company. He served as the repair section chief on Guadalcanal, where he saw little action but contracted malaria. Not long after reaching the shores of Betio, the burly 31-year-old Carlsen was shot in the abdomen, then in the head. He died on 20 November 1943.

Harry Carlsen was reported buried in Grave 31, Row B of the East Division Cemetery on Betio (also known as Cemetery 33). His remains were actually found in this location, but without a marker (removed as part of cemetery’s “beautification” by the Navy) or any identifying belongings, the 604th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company decided that they couldn’t identify the body. Unknown “X-82” similarly mystified technicians at the Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii, who described a man taller and older than most Marines, with traces of reddish-brown hair. The remains were buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in March of 1949.

The search for Harry Carlsen’s remains made the news, first in 2010 as JPAC and History Flight planned or reported on missions to Betio, and again in 2013 as the seventieth anniversary of the battle approached. Both Mark Noah of History Flight and Chief Rick Stone opined that Carlsen was buried as an unknown; Stone went so far as to insist that X-82 was, in fact, Harry Carlsen. Another four long years elapsed before the grave was exhumed, and DNA testing validated Stone’s long-held claim. Additional evidence recovered by a History Flight expedition in 2013 helped to confirm the findings. (Read the DPAA news release.)

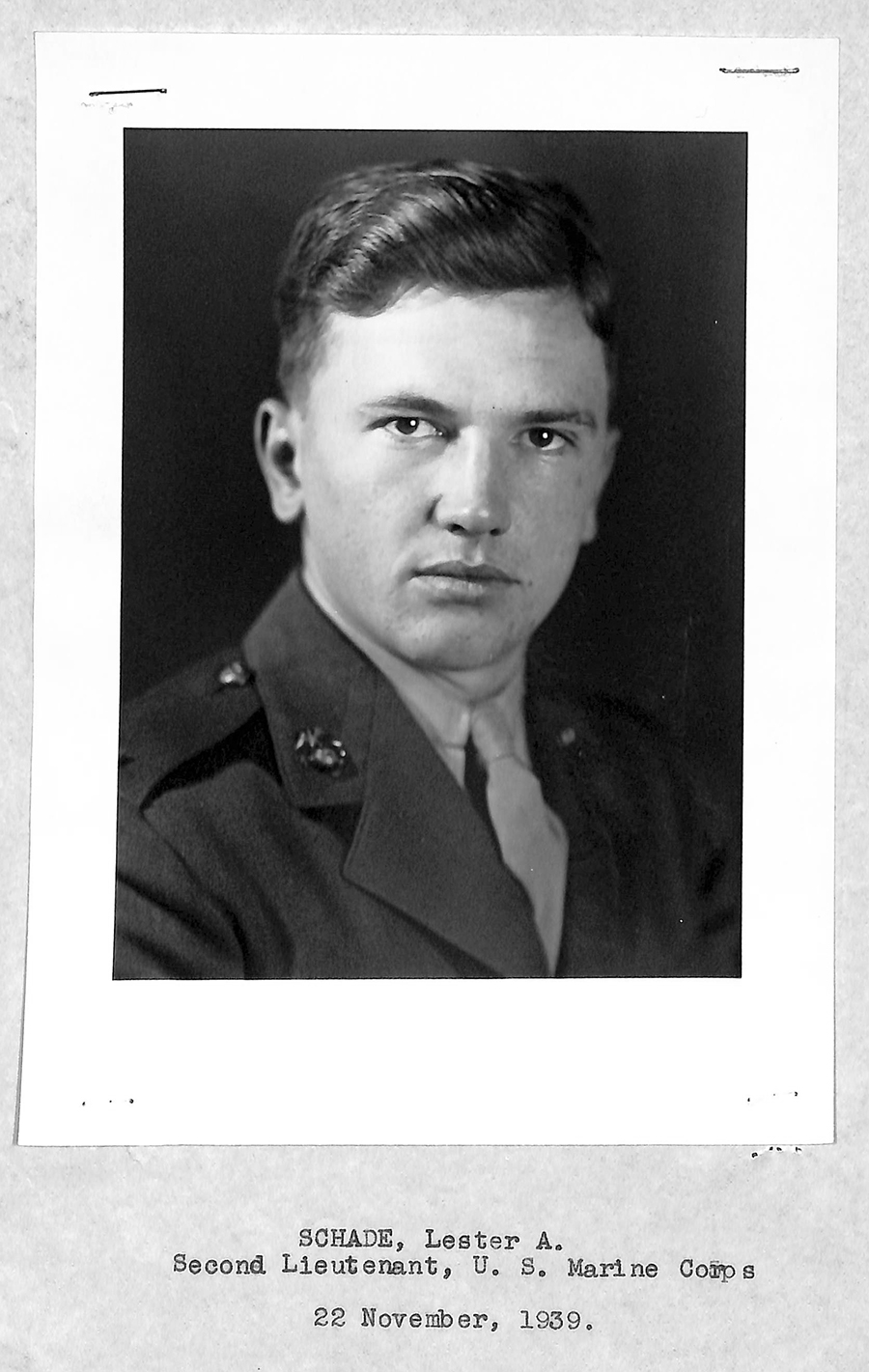

Captain Lester Albert Schade had a long and terrible war. A native of Holton, Wisconsin, Schade joined the Marine Corps in 1939, shortly after his graduation from the University of Wisconsin. After completing officer training, he was assigned to duty with the First Separate Marine Battalion at Cavite, Philippine Islands. The outbreak of war saw Schade’s unit absorbed by the 4th Marine Regiment; he became an officer in Company I, 4th Marines, and served with the mobile Marine Air Warning Detachment.

Captain Lester Albert Schade had a long and terrible war. A native of Holton, Wisconsin, Schade joined the Marine Corps in 1939, shortly after his graduation from the University of Wisconsin. After completing officer training, he was assigned to duty with the First Separate Marine Battalion at Cavite, Philippine Islands. The outbreak of war saw Schade’s unit absorbed by the 4th Marine Regiment; he became an officer in Company I, 4th Marines, and served with the mobile Marine Air Warning Detachment.

Lieutenant Schade was eventually captured in the fall of Bataan, survived the infamous Death March, and spent more than two grueling years enduring the depredations of POW camps in the Philippine Islands before being selected for a prisoner draft bound for Japan. Along with thousands of other POWs, Schade was herded aboard the “hellship” Oryoku Maru – a former passenger cargo ship converted to a prisoner transport. The ship was not marked as carrying POWs, and was attacked by American aircraft on 15 December 1944. Schade survived this ordeal only to be packed onto another hellship – the Enoura Maru – and sent to Formosa (modern-day Taiwan).

On 9 January 1945, American aircraft struck again, dropping bombs on ships in Takao Harbor. The Enoura Maru was badly damaged in this attack, and an estimated 400 prisoners of war were killed. Lester Schade was among them. The bodies were brought ashore for burial, and many official reports – including Schade’s Individual Deceased Personnel File – claimed that the remains were all cremated. Schade was declared non-recoverable; he was also honored with a posthumous promotion to captain.

After the war, a mass grave was located near Takao Harbor; when all the bones were tallied, experts believed they had the remains of 344 individuals. The vast majority were not individually identified, and were instead buried in mass graves in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. Ted Darcy’s WFI Research Group first argued that Lester Schade was identifiable in a 2015 article. Schade’s exhumation and identification on 26 July 2018 proved them right. (Read the DPAA news release.)

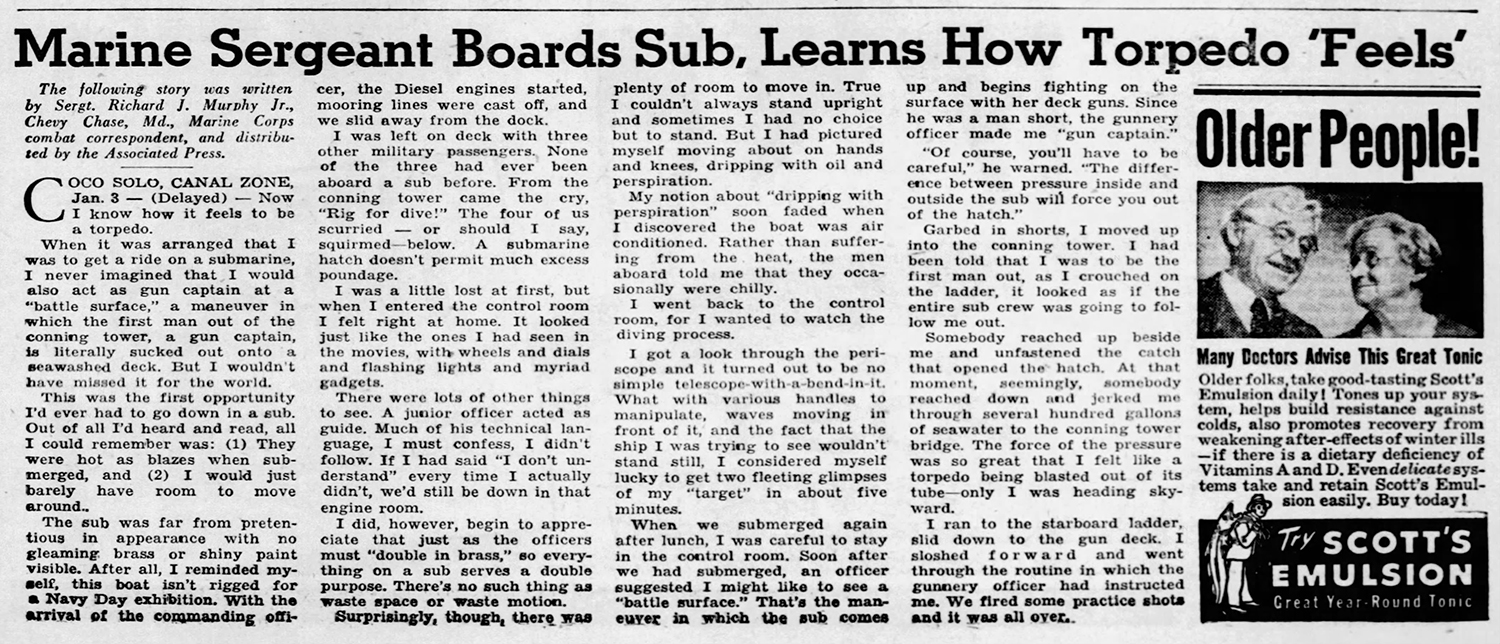

Staff Sergeant Richard Joseph Murphy wanted to be an officer, but poor vision thwarted his aims. Undaunted, he joined the Marines as an enlisted man, where his degree from Georgetown University and civilian job with the Washington Star soon translated into a role in public relations.

His first assignment with the barracks detachment at Coco Solo, Panama, gave Murphy the chance to describe some of the more mundane details of life in the service. He submitted stories about recreation (“Marines In Canal Zone Read Everything They Can Find As Chief Diversion”) and mock jungle battles waged against nearby Army troops. His most popular effort was penned after a trip to the nearby submarine base. “when it was arranged that I was to get a ride on a submarine,” he mused, “I never imagined I would also act as gun captain at a ‘battle surface,’ a maneuver in which the first man out of the conning tower… is literally sucked out onto a seawashed deck.” The “opportunity,” perhaps dreamed up by the sub’s crew as a trick to play on their Marine guest, was met with Murphy’s characteristic good humor. “I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.”

In the late summer of 1943, Murphy was transferred to the Fleet Marine Force and joined Headquarters and Service Company, 6th Marines in New Zealand. From stateside PR flack, his role transitioned to that of combat correspondent – and the 6th Marines were shortly bound for Tarawa. He related few of his own experiences, but burned up his typewriter keys with heroic stories of hometown heroes chasing stragglers across the islands of Tarawa and into a last stand on Abemama.

A selection of Murphy’s “hometown hero” stories, published in 1944.

At Tarawa, Murphy went in with the mopping up units. In his next invasion – Saipan – he would be in one of the first waves.

Exactly what happened to Staff Sergeant Murphy is not known for sure. According to an article in the Marianas Variety, one of the men in Murphy’s landing craft fell overboard during the landing operation, and Murphy leaped in to rescue him. Somewhere in the confusion and chaos of 15 June 1944, Richard Murphy went missing; nobody ever saw him again, and after several months he was declared dead.

A few days after the landing, an unidentified body was brought to the Second Marine Division cemetery on Saipan and buried in Plot B, Grave #3 as an unknown. This man was exhumed in June 1948, designated X-15, and brought to a laboratory in Manila for identification. He had nothing left but a pair of brown GI shoes, size 10.5. His dental chart and vital statistics were taken, and he was buried – once again, unknown – in the Manila American Cemetery at Fort McKinley.

Ted Darcy’s WFI was on the case, and in 2015 claimed that X-15 was none other than SSGT Richard Murphy. Kuentai-USA, a Japanese group specializing in Mariana Islands recoveries, compared Murphy’s dental records with X-15 and agreed with the findings. Again, several years passed before action was taken, but Richard J. Murphy has finally been identified as of 25 July 2018. (Read the DPAA news release.)

Ted was the first MIA researcher I ever encountered when I started this project, and I recall having conversations with him about SSGT Murphy as far back as 2013. We haven’t always seen eye to eye since then, but Ted refused to give up and stood by his research for years, and you have to respect the courage of conviction. Hopefully this is the start of a string of successes for WFI.

Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class William Horace Blancheri, age 19 and from Los Angeles, California, was also accounted for this August. “Bill” Blancheri was active in the band and ROTC at Abraham Lincoln High School; he entered the Navy just days after his eighteenth birthday. Assigned to the Second Battalion, 2nd Marines, Blancheri was killed in action on 20 November 1943 during the initial landings on Betio. He was buried as an unknown in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, and finally identified on 14 August 2018. Read the DPAA news release.

Other Marines recently accounted for from Tarawa include PFC Robert L. Zehetner (F/2/8th Marines), Cpl. Claire E. Goldtrap (A/2nd Amphtracs), PFC Paul D. Gilman (M/3/8th Marines) and PFC William F. Cavin (F/2/8th Marines). More to follow on these individuals.

Identified in May but not announced until July of this year was PFC Robert Kimball Holmes. The nineteen-year-old from Salt Lake City was assigned to the USS Oklahoma and died on 7 December 1941 when his battleship sank at Pearl Harbor. Holmes’ remains were recovered when the Oklahoma was raised, and buried in a mass grave in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. Holmes is the third Oklahoma Marine to be identified, following 2Lt. Harry H. Gaver and Pvt. Vernon P. Keaton. He was buried in Salt Lake City Cemetery on 20 August 2018.

Finally, I traveled to Philadelphia to attend the service and reinterment of Private Emil F. Ragucci (E/2/2nd Marines), another young victim of the battle of Betio and who was identified in a joint DPAA/History Flight effort in November of last year. Ragucci was one of five brothers in uniform during World War II – three others would serve in the years after the war – and his death at Tarawa was followed in a few weeks by the loss of Nick Ragucci at Monte Cassino. Two surviving Ragucci brothers, Dominic and Victor, were present at Holy Sepulcre Cemetery to welcome Emil back home. My wife and I had to get back on the road immediately after the ceremony, but I did manage to hand over a few framed copies of the Tarawa Requiem to the brothers as a memento.

And I wish I’d been able to attend the Arlington funeral of Herman Mulligan, who was serving with L/3/22 on Okinawa when he tossed a grenade into what turned out to be a Japanese ammunition bunker. The twenty-one-year-old from Laurens, South Carolina was thought to be blasted beyond recognition, but thanks to the investigative work of Dale Maharidge (whose book Bringing Mulligan Home details his personal quest) and Robert Rumsby, the remains formerly designated X-35 in the 6th Marine Division Cemetery, Okinawa were disinterred from Manila and identified as Mulligan’s. The New York Times ran an excellent piece on Mulligan’s saga, which is well worth a read.

And I wish I’d been able to attend the Arlington funeral of Herman Mulligan, who was serving with L/3/22 on Okinawa when he tossed a grenade into what turned out to be a Japanese ammunition bunker. The twenty-one-year-old from Laurens, South Carolina was thought to be blasted beyond recognition, but thanks to the investigative work of Dale Maharidge (whose book Bringing Mulligan Home details his personal quest) and Robert Rumsby, the remains formerly designated X-35 in the 6th Marine Division Cemetery, Okinawa were disinterred from Manila and identified as Mulligan’s. The New York Times ran an excellent piece on Mulligan’s saga, which is well worth a read.

Meanwhile, MissingMarines itself has reached a milestone or two; there’s some news about the book I’ve been writing (it’s called Leaving Mac Behind and yes, it’s going to be a real thing) and a great new work from Clay Bonnyman Evans, Bones Of My Grandfather about the successful search for his grandfather’s grave on Tarawa. More to come, now that we’ve busted the rust on the post feature!

My Uncle Bud …..Harry A. Carlsen T/Sgt USMC will be buried Oct.13,2018 at 11:00 AM at the Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery, Elwood , Illinois with full honors. His name and some history about him is stated above. Thanks for the nice write up! Let’s bring them ALL home!